When I turned 18 in May of 1999, Pastor Johnson finally granted me parole – I mean, graduation – from the program and return home. My parent excitedly attended my grad ceremony there the next month and brought me back home to the rest of my family where I belonged. After 2 1/2 years of my youth lost surviving in…whatever this was, it was finally over.

Graduation day was the last time I was physically confined to Canaan Land. My sentence was served. First order of business once I was free? A home-cooked feast of mom’s spaghetti and fried perogies, followed by a cinnamon bun the size of my head, smothered in cream-cheese icing. My body didn’t just eat – it inhaled. It took a few days for the normal comforts of life to feel real again. A long soak in a hot, soapy tub? Divine. My own bed? Heaven. I slept like the dead for 12 to 20 hours at a time. Apparently, enduring a teenage gulag takes it out of you.

After being held for over two years in a “one-year” program designed for adults – while I was still legally a child – I was released into the wilds of the real world. The transition was… jarring. Imagine being dropped onto planet Earth after living off-grid as a lumberjack-in-training in the backwoods of Saskatchewan since age 15. That was me. So I made myself a list. Three things I knew I had to do if I was going to survive this bizarre simulation called adulthood:

- Learn to function in the real world

- Get a job

- Earn my GED

The outside world was so magical and wonderful and scary at the same time. After living the past 2+ years of my life in isolation in a closed-community like Canaan Land, everything felt foreign and exciting. Every stranger I passed on the street heard me chirp a cheery “hello!” as I awkwardly reintegrated myself into a society with more than 5 people in it. As unequipped as I was, I tried like hell to fit in and pretend like I was part of the real world even if I felt like a total fraud. My imposter syndrome was off the charts.

As unequipped as I was, I tried like hell to fit in and pretend like I was part of the real world even if I felt like a total fraud. My imposter syndrome was off the charts.

It didn’t take long to learn that before anyone would pay me to do anything remotely productive, I’d need something called a Social Insurance Number—apparently, the golden ticket to employment in Canada. Dutifully, I followed the bureaucratic breadcrumbs: filled out the forms, mailed off my details to the government, and waited for my shiny new SIN card to arrive like a prize in the mail.

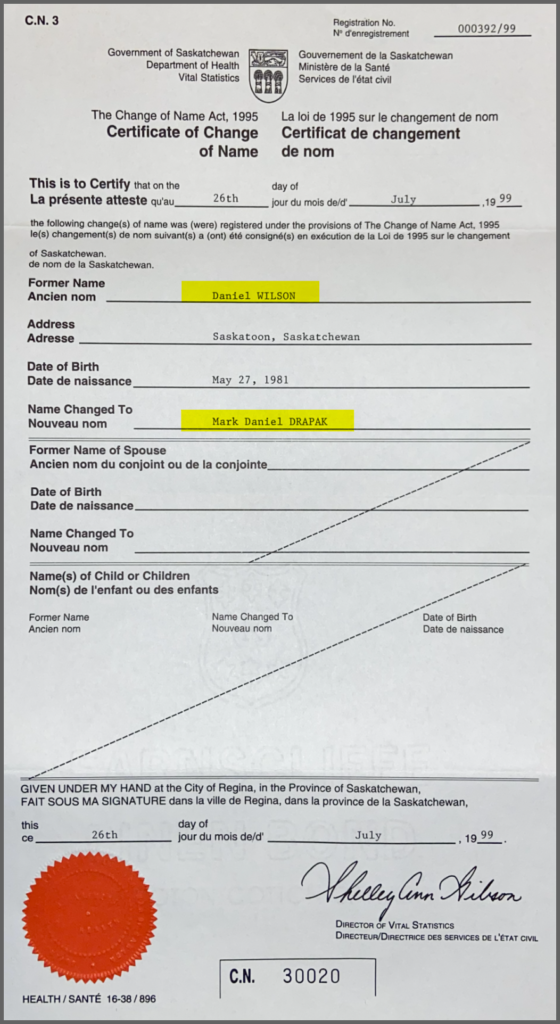

Weeks passed, and finally, a letter arrived—not the card, but a reply. As I unfolded it, I felt that odd little tingle you get just before your life takes a weird turn. The letter was blunt, clinical, and utterly disorienting: according to official records, no one named Mark Drapak was ever born in Saskatchewan. Which was news to me, given I had lived my whole life under that name. My application was denied, because, technically, I didn’t exist.

I stared at the page, reading it again and again, hoping the words would rearrange themselves into something more comforting. No luck. Instead, I learned that the identity I’d known all my life had been overwritten by some mystery man named Daniel Wilson, whom the Department of Vital Statistics was now insisting I was. Daniel Wilson? Who? And more importantly – if I’m Daniel, then what happened to Mark Drapak? As the realization set in, my head spun. I wasn’t just being rejected by the job market – I was being ghosted by reality itself. I had stumbled into an identity crisis with government-issued receipts.

I was being ghosted by reality itself.

The mind-renewal mantras surged through my thoughts like a holy chant on loop. The Canaan Land program made us “confess” these every day over and over again. “I’m a new creation. A brand new man. Born again. The old Mark? Dead and buried. Transformed by the renewing of my mind. Clothe myself in the new self. Behold, all things are made new.” Had I conjured this into being by sheer belief? Did it really work – did the program over the past years actually hit the reset button on my life?

It became increasingly clear that I needed to have a serious talk with my parents – some truths needed untangling. Apparently I was born when their relationship was on the rocks, and that was the name that was written down on the paperwork. After some soul-searching and mental gymnastics, I arrived at a strange yet obvious conclusion: I needed to legally change my name to reflect the identity I had carried my entire life. The idea felt alien. I had never even heard of anyone doing this. But then again, nothing about my adolescence had made much sense either – why should this be any different?

I submitted myself to the bureaucratic gauntlet laid out by Saskatchewan’s Vital Statistics. One milestone involved swearing an oath before a Justice of the Peace. So, clutching my paperwork like a nervous schoolkid, I presented my application. He instructed me to raise my hand, swear my truth, and sign the documents.

As my pen scrawled the only name I had ever answered to – Mark Drapak – the Justice suddenly interrupted. “Wait,” he said, “you just signed the form as ‘Mark Drapak,’ but that’s not your current legal name he reminded me. You’re Daniel Wilson – you need to sign that name on the change form.”

And just like that, in a moment thick with irony, I signed Daniel Wilson – a name that had never really been mine – so that I could finally become who I truly was.

“I signed Daniel Wilson – a name that had never really been mine – so that I could finally become who I truly was.”

One month later, the government gave its blessing. My name change was official: I was legally Mark Drapak. Armed with my new identity, I reapplied for my Social Insurance Number and soon received confirmation. That little card with my real name on it felt like a golden ticket – finally, I could look for work and try to blend into the elusive world of “normal.”

Of course, “normal” had no idea who I was and I wasn’t quite sure how to sell myself to potential employers. With the social grace of a wilted houseplant, I stumbled through unsuccessful job applications and interviews while studying for my GED. Then, out of the blue, an usher from our church threw me a lifeline: a part-time job! The kicker? I was hired as an arborist – chopping down trees, just like I’d been forced to do for two and a half years in the gulag. Life, apparently, has a twisted sense of humor.