The day before everything changed, Shian Klassen – a man of supposed faith – threatened to strip me of everything I loved. I was fifteen. A child. And he told me that if I didn’t comply, I’d be excommunicated – not just from Christian Centre Church, but from my school, my community, and even my own family. Imagine being told that one refusal could erase your entire world.

During that meeting, Jim Lee watched me closely. He seemed to notice that I was fiercely protective of someone. For anyone who knew me back then, it was no mystery who that was: my little brother, Mike. We were inseparable. Two halves of one childhood, bound together by love and survival.

The next day, Jim summoned me. He wanted to know why I wanted nothing to do with the Canaan Land program, a so-called “religious rehabilitation” centre tucked away in the remote northern Saskatchewan woods. I tried, and failed, to explain:

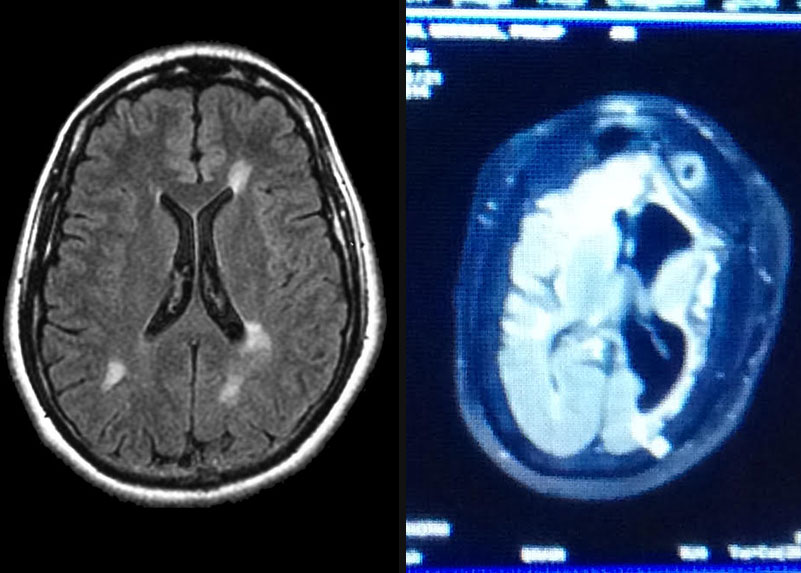

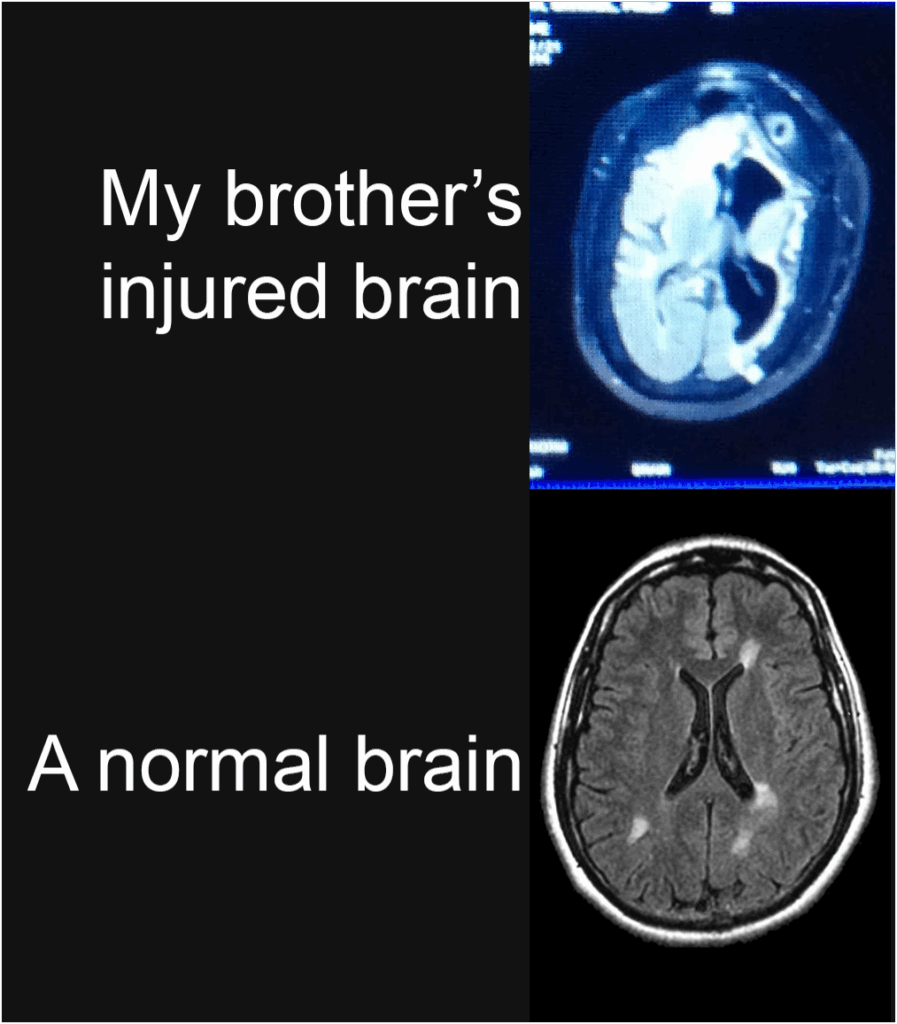

my single parent needed me, that my disabled little brother needed me, that home was where I belonged, not some remote religious compound that already felt like a gulag for the unwanted.

Just the day before, I had pleaded with Shian to understand that sending a 15-year-old child to a program for adults was madness. But compassion and grace was never part of their doctrine. When I tried to make Jim Lee understand, my voice trembled: “Please, ‘Brother’ Jim. I need to help my single parent take care of my disabled little brother. He needs me at home.”

“Please, ‘Brother’ Jim. I need to help my single parent take care of my disabled little brother. He needs me at home.”

Jim didn’t flinch. His face stayed as cold as the winter ground outside. Instead of empathy, he sermonized, claiming that my family would “be just fine without me” if I only had enough faith. God, he said, would take care of them. I just needed to “use my faith” and “stop thinking of myself.”

My parent’s first letter to me in Canaan Land arrived a month later, but it was confiscated and labeled “contraband.” It described their depression, their stress, and how my sudden removal had shattered the rhythm of their life and work. I wasn’t allowed to respond. So I couldn’t tell them that I planned to endure it all – every day, every humiliation – just to make it home again as soon as I could. That was my only plan: survive the year and return hope to help as quickly as I could.

Months later, Jim Lee called me into his office. My parent was in the hospital. Their appendix had ruptured; likely from the relentless stress of it all. He promised that when we went to church in Saskatoon that Sunday, I could visit them afterward.

Sunday couldn’t come fast enough.

I had thought I would have more time before I’d have to face my parent again. Time to build myself back up, to fortify the torn edges of my heart. But hospitals don’t give you that kind of time. They demand presence and rushed arrival. Plus, we had to push these things aside and discuss an even more important matter – who is taking care of my brother!

Hospitals don’t give you that kind of time. They demand presence and rushed arrival.

Finally Sunday came and the painfully long church service was over. Entering through those hospital doors, I was swallowed by the sterile brightness and chemical smell in the air. It occurred to me as I walked the hallways, that my parent had seemingly pushed me away, cut me out, and yet here I was, summoned back by sickness. Part of me resented even the instinct to go there. I hated how automatic it felt to show up when I could have returned the cold favor and called it “karma”. But I couldn’t.

When they realized I was standing there, I folded my hands tightly in front of me. I didn’t trust myself to touch theirs. What if I forgave them too easily? What if my anger melted away with one small gesture? So I stood still and asked the only question that mattered: “Where is Mikey?”

They answered immediately: “Strangers from Social Services are with him at home.” Strangers were now caring for my disabled brother because both of his caregivers – his only family – had been taken from him: one hospitalized, one imprisoned in a religious gulag.

We spoke for a while about everything except what truly mattered. They told me about the pain, the doctors, the cold nights. I asked polite questions, as if we were distant relatives instead of a parent and child torn apart. The words we needed most – “You hurt me,” “I miss you,” “I’m sorry”, – hung heavy in the air, thick enough to choke on. Neither of us spoke them.

The words we needed most – “You hurt me,” “I miss you,” “I’m sorry”, – hung heavy in the air, thick enough to choke on. Neither of us spoke them.

I wasn’t allowed to go home. Not for my brother’s care, not for my parent’s recovery. I stayed in Big River – a captive in a faith-based prison. My brother’s 13th birthday came and went without me. He celebrated with the kind strangers while I sat a couple hundred of kilometers away, forced to pray to a God who never seemed to hear.

A couple of weeks later, our parent returned home to care for my brother again.

In the decades since, I have never missed a single one of Mike’s birthdays. Not one. Each time we gather, and his face lights up with pure, radiant joy, I feel something heal. The love between us – the kind that cults can’t poison and time can’t erase – fills the space that grief once occupied. And sometimes, when I see that same joyful smile, I think about those strangers from Social Services who stepped in when no one else did. The ones who showed my brother compassion when the cult showed us none. For that, I will always be grateful. And for my brother, my best friend, my heart – I will always be home.